Classes have such different cultures. I think factors such as size, the people in the room, and the time of day play into it. I have classes as small as 12 students and as large as 23 students! I have 9th grade students and 10th grade students. Both groups in the morning and in the afternoon. Part of teaching well is to be able to work with the individual student personalities, as well as the personalities of the class as a whole.

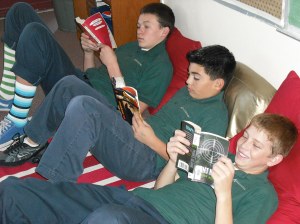

I have a HUGE class of 10th graders, and they are full of personality. I’m trying to figure out how to best work with them and to get them to “get it.” A lot of their work will be independently driven, with ample time to work in class. However, it takes them a long time to settle down. They aren’t “bad” or disrespectful, but they have a ton of energy. My concern is that they’ll miss a lot of work time opportunities in class because they distract each other. Hopefully, once the class gets into full swing they’ll begin writing as soon as they walk in.

I began this blog with my larger class, using my personal blogging as an example for the students. I am not sure if what I had to say made an impression or if how I went about communicating in class did, but overall the class went better. The students, while it still took them a bit of time to get to work and quiet, were working diligently. Sure, I had a couple students who I had to take painful efforts to remind and remind and remind and remind that they needed to be working…but they eventually got to work. I think I’ve figured out how to work with this class’s personality!